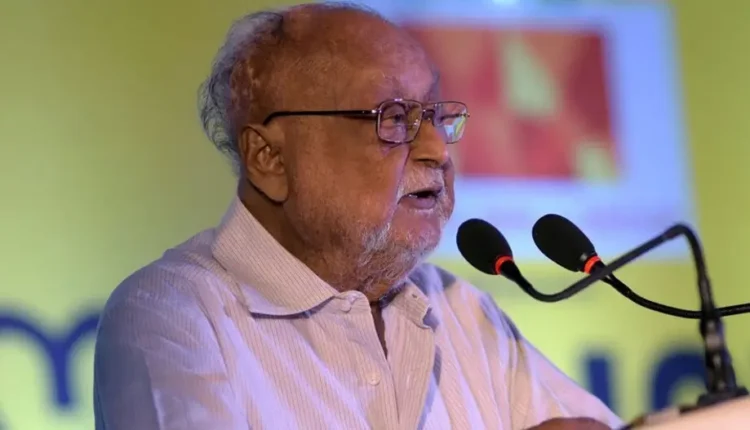

The Master of Imagery & Empathy Passes Away

Jayanta Mohaptra who passed away on 27th August at the ripe old age of ninety-five leaves behind a legacy that is both beguiling and inspiring. As a fledgling fourteen, Jayanta joined the Ravenshaw College in 1942 to study science and Physics. The iconic college established in 1868, has a history which is synonymous with the history of modern Odisha. It throbbed with its neatly laid out tennis courts and canons, sedate and impassioned, positioned in front of the portico. This was the year when World War II was at its crescendo & Gandhi gave a call for Quit India on 9th August 1942. Jayanta was slowly and inexorably got drawn in to the movement. He writes in Ravenshavian (2009), a commemorative volume: “I recall the silent murmurs of the grassy lawns, the smiles of my Professors that never failed to reflect the severe light of their knowledge. My heart resembled in part the air raid shelter, the dark and dismal room underground; a place where footsteps of my youth trembled on its verge, then took green wings and leapt in the skies”. Indeed, the story of Jayanta, who started his career as a Physics teacher leapt rather slowly to become the most innovative, purposive and Anglophile poets of modern India. He along with Ramanujam, Parthasarthy& Ezekkiel laid the foundations of Indian English poetry.

His first book “Close the Sky, Ten by Ten” came out in 1971. Since then there has been a steady flow of poems, culminating in to 16 volumes in English, as well as short stories and essays. He also established and edited the journal “Chandrabhaga”. The sheer energy, determination and commitment required to carve out a literary career out of his unpromising beginnings are remarkable. He decolonized English poetry and enthusiastically evoked Indian culture and tradition. His poems Indian Summer & Hope are considered classics in modern Indian English literature. Taste for Tomorrow, Hunger & Relationship won him enormous accolades. The oppressive claustrophobic, with its death, disease & decay, beggars and poverty pervades his work. Two important quality of his work, however, stand out. One is his innate humanitarianism, his empathy for the underdog; violence, oppression, poverty among others and the other is his metaphorical imagination, which is highly developed and extremely fertile.

Here is a sample of his unique use of imagery:

“At Purl, the Crows

The One Wide street

Lolls out like a giant tongue

Five faceless lepers move aside

As a priest passes by.”

Relationship, a major work of his, uses the Konark Sun temple as a focus for the exploration of the Orissan past. He writes in his most famous poem Hunger (1976):

“Once again one must sit back & bury the face

In this Earth of forbidden myth

The phallus of the enormous stone

When the lengthened shadow of a restless vulture

Caresses the strong and silent deodars in the valley”

He is also known for his splendid four Puri poems: “Sky without sky” which appeared in the Punch magazine. He wrote:

“When hope becomes a bird of prey

Motionless, hanging above the good earth

As if it were its sole guardian,

When we don’t like ourselves

When there is so little physical unlikeness

Between one thing and another.”

Interestingly the role of stones occupies a pivotal place in his poems. In his eponymous work “Relationship” (1981) he writes:

“My existence lies in the stones

Which carry my footsteps from day into another?

Down to the infinite distances

When darkness falls the stones come closer towards us”

Social reality and depicting its innards is one of the core themes of Jayant Mohapatra. He deplored the poets who wrote about the urban areas without caring for the distress of rural India. In his poem Dusk he wrote:

“As in film, the stock of freedom

Freedom from want, social justice

Poised over the bleeding heartland

And in the earth sounds of bare feet Sloping the village road

The famine is in the air

A reality which will offend the gods”

He was truly concerned about the harsh reality of acute poverty and social injustice in rural India. In this aspect he had a close parallel in film maker Mrinal Sen, who made Akaler Sandhane, depicting how rural life has not changed much from the time when Bengal famine struck.

He was once asked the relationship between his background in science and opting to write poetry, Jayant replied: “I suppose that the study of physics taught me a certain discipline in the use of words in a poem. Physics taught me to write in a concise, not to use unnecessary words in a poem.

Syd Harrex ,a literary critic , observes that Mohapatra’s imagination is of the type that is Jungian. Many of his poems seem to be a result of a quest for verbal surface indicators of primordial, pre-linguistic, dream-layered experiences. It’s true that Moahpatra uses myth often in his poetry and the myth is intimately connected with the Jungian ideas of archetype and the collective unconscious. His poetry unravelled many facets of post colonialism as haunting past and a search for identity and roots. He lived a full life and was a man of enormous conviction. He returned the Padmashree award he received in 2009 in 2015 to protest against rising intolerance in India. He was never a fence sitter, like Girish Karnad , the thespian of theatre , who flaunted a placard’ I am a Naxal’, protesting against ruthless victimization of dissent . Chinua Achebe, the famous African writer, wrote: “Until the lions have their own historian; the history of the haunt will always glorify the hunter.” Odisha was blessed that the history, tradition and culture of Odisha had the benefit of a post-colonial writer like Jayant Mohapatra , who used imagery & empathy to lift Indian writing in English to incredible levels.