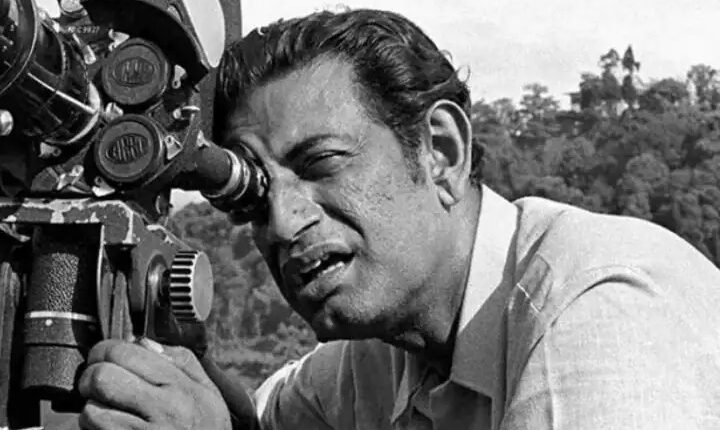

Satyajit Ray at 101 : Cinema’s India in Black & White

He was an oddball in the Calcutta of 60s, teeming with anarchists, Trotskyites, Mao devotees and loonies believing in flat earth. The intellectual to population ratio was high even by the usual Bengali standards. Yet he stood out, literally for his height, During the release of the Apu trilogy (1955-59), his cinematic apotheosis was complete. In the 60s & 70s his reputation became stratospheric. PM Indira Gandhi, four years older but an intrepid admirer & friend, scrupulously invited visiting foreign dignitaries to private screening of the national icon in a way that no Indian art personality ever had been; with the solitary exception perhaps of Tagore. Santiniketan & Tagore connected them both. Indira joined Shantiniketan in 1934 and sang hymns, meditated and took to Manipuri dance, earning encomiums from the Gurudev . Satyajit Ray joined Santiniketan in 1940 and discovered oriental art, Japanese woodcuts, & Chinese landscapes. Binod Bihari Ray taught him how the small details in Indian art signify bigger meaning, a quality that his films would later demonstrate. His passion for western classical music was triggered by his German Jewish Professor. Penelope Houston wrote: Ray’s Bengal would remain Cinema’s India!

Ray’s contemporaries like Ritwick Ghatak and Mrinal Sen were the local flavour at best. Talents like Adoor Gopal Krishna, a later day Ray of the South, Shyam Benegal had nor risen yet. Even if they were, it would not have made much of a difference. For nobody else in the Indian film industry is as multi-faceted as Ray. Much before the release of the Apu trilogy, his reputation as a book designer stood on a wooden plank. Renoir while shooting his film, River (1951) in solicited his help for finding locations. He remained a great influence, just as De Sica ‘s Bicycle Thief (1948) which represented Italian neorealism at its best. Children used to skip their home work to read his Feluda stories as they appeared in Puja annual numbers. He was a man of great social charm in every gathering, from the enlightened chic to the local wana be. There was an Englishness in his personality. More than his accent, which had a BBC quality about it, it was his sharp understatement that sounded alien in the typical Indian social evenings.

In a career spanning 37 years with 29 feature films, Ray has left behind a body of work, an array of interests which can be the envy of any artistic person. However, the Apu trilogy remains the corner stone of his oeuvre. The Apu films touched the creative minds as an overpowering coming of age story, in perfect tune with the genre of adolescent fiction that was to later explore in TV cartoon stories, like the Simpsons. Charulata (1964) is considered as his finest film and was also his personal favourite. Based on a Tagore novel Nastanirh, Ray is elegance personified when dealing with gentle emotion; a bored housewife with writerly ambitions, the young male cousin supremely conscious of his own charm and Kishore Kumar crooning ‘Ami Chini go Chini Tomake Ago Bideshini’ . It’s a cultural crescendo that Ray could alone conjure.

Ray was a picture of a dictator on the set, his words having the ring of an army commander. His production staff were his disciplined troop. He was terribly hands on. He had sketched how a possessed woman would look like in the film Devi. Sharmila had to only emote. Elia Kazan described the film as ‘poetry on celluloid’. Victor Banerji who performed in Ray’s Ghare Baire , when asked to compare Ray with David Lean merely said : You don’t compare autocracy with democracy! At the time of making Ghare- Baire , he had a paralytic heart attack in 1983. The tall man was crouched between the Arriflex camera as it rolled on a trolley. He was not the same director again. His shot his films indoors thereafter. They lacked the magical splendour of sunshine and rains or searing whistling of a train of Pather Panchali or the classical precision of Charulata. His best films were shot in Black & White. Indian cinema had been drawn drenched in colours long before Ray began loading Eastman colour rolls on his camera. It was a trade off in which colour added glamour but took away from cinema its role as a critical observer of reality. When Spielberg, the messiah of techno cinema had to tell a story like Schindler’s List based on a Jewish German’s attempt to save the victims of the Nazi holocaust, he chose black & white, not colour. Ray had an obligation to chronicle joys and sorrows of his people. He accomplished it, literally in black and white.

At the beginning he worked with classical musical maestros like Ravi Shankar, Vilayat Khan & Ali Akbar Khan . He found that their first loyalty was to musical tradition and not to his film. He cut his teeth in western classical music in Santiniketan, and Beethoven was his favourite. Music came natural to him. He learnt freeze frame shots from Trauffaut and jump cuts from Goddard. But he eschewed Hollywood’s liberal use of big close ups, in order to emphasize glamour or to dramatize details of the acting. Many considered him to be glacially slow, moving like a majestic snail. He was like Bergman or Antonioni who imposed his own rhythm on the audience. He was like a river, big and flowing. I was lucky to see the master in the pink of his prowess introducing Akira Kurosawa whose film Dersu Uzala was being screened in Vigyan Bhawan on 3rd January 1977. It was the height of emergency. Mrs Gandhi had come to felicitate Kurosawa and recounted how Nehru, had made her watch Kurosawa’s epic film Rashmon (1950). But the best compliment came from Akira: Not to have seen cinema of Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or moon. Indeed, Ray is Cinema’s India, in black & white. It was the finest cocktail of fascism and culture; I was fortunate to watch.

Satya Misra is a film buff